What’s at stake for the EU in Ukraine ?

The NATO summit failed to address the crucial problem of the European Union’s eastern borders.

One could be forgiven for believing that this week’s NATO anniversary summit in Washington was about indulging the US’s obsession with global hegemony in international affairs.

The West’s Cold War-era foe Russia has again occupied a big share of the summit participants’ attention. Next came the effort to convince NATO‘s European members that China - which got mentioned no less than 14 times in the final communiqué - was fast becoming the main menace to the West, and that the alliance should change its focus from the Atlantic to the Indo-Pacific instead.

Less obvious to observers and absent from official discussions at the summit was the EU’s own stake in the ongoing Ukraine war. Far from being of secondary importance, the answer to the question of “what’s in it for EU states in the current conflict between NATO and Russia ?” was obscured by US rhetoric concerning the fight of democracies against the autocracies of Eurasia.

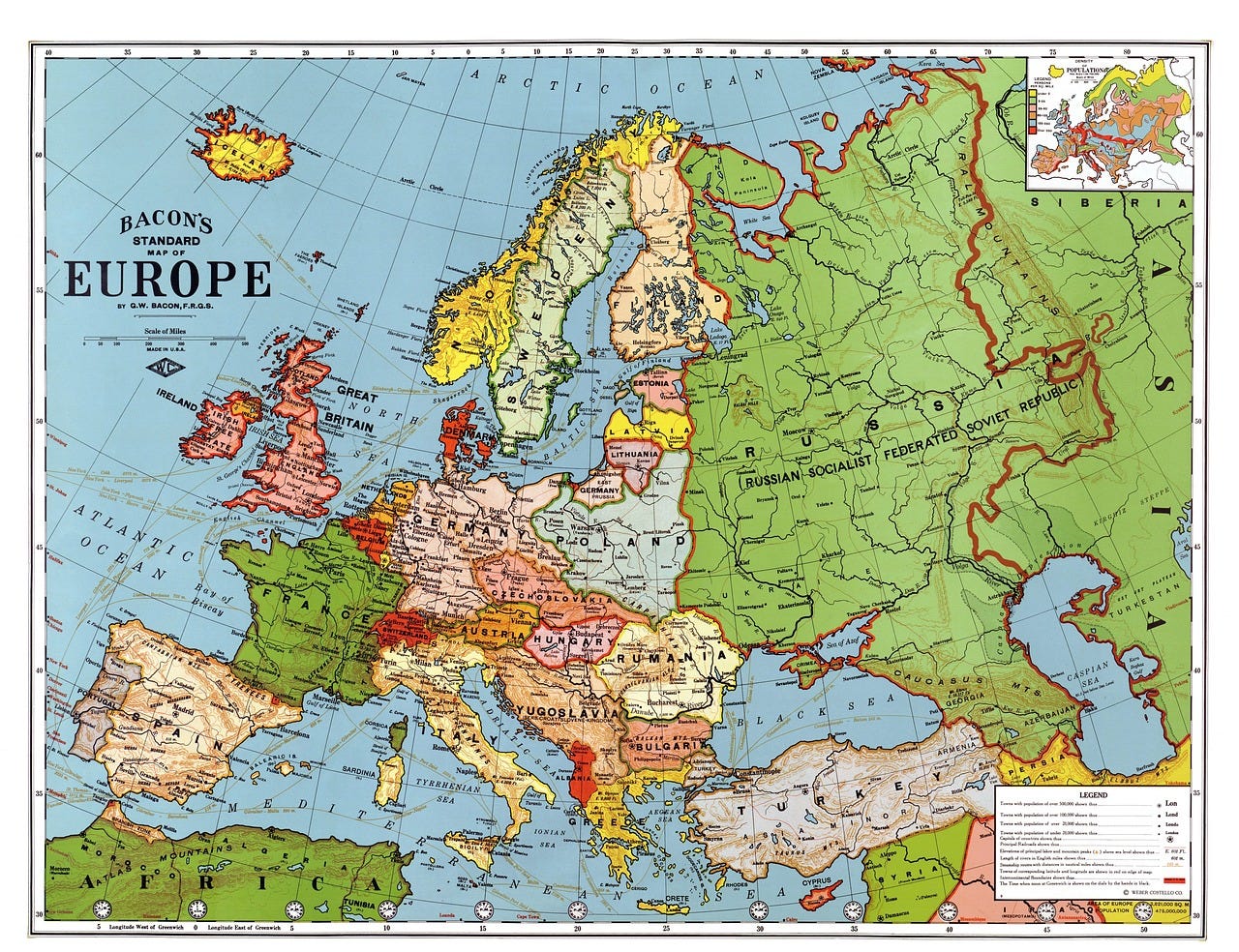

The crux of the matter, however, is simple. It has to do with historic geopolitical efforts to push Europe’s borders much further to the East than where they rested when the USSR’s implosion took place in 1991.

The constant drive to expand Europe’s borders eastwards was initially backed by the Catholic Church during the Middle Ages. At the time, it led to numerous military confrontations with Russia, already a major power that was trying to extend its borders westwards, as well as southwards, where it came into conflict with the Ottoman Empire.

In modern times, the role of expanding Europe’s eastern borders was undertaken by France under Napoleon Bonaparte in the 19th century and by Germany in the 20th century during the Nazi period.

As one of the victors in the Second World War, the USSR succeeded in pushing its western frontiers further than before, incorporating lands that hitherto belonged to Poland, Germany, Czechoslovakia or Romania. After its demise in 1991, a host of newly independent states such as the Baltics, Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia appeared on the map. The geostrategic competition to incorporate them - either into the Russian state’s traditional sphere of influence, or within the European Union’s political and military structures, such as NATO - started anew.

Ukraine is the big prize of the EU’s drive eastwards at the expense of Russia. As I have noted elsewhere, this confrontation started as early as 2004, it increased in intensity in 2012 and burst into the open during the Maidan so-called revolution of 2014, when Russia decided to annex Crimea and support the fight of the Russophone population in the Donbas against the Kiev regime.

As we all know by now, NATO’s and the EU’s refusal to stop their expansion drive in Ukraine has finally led to war in 2022 between Russia and the regime that was installed in Kiev with American help during Maidan.

The fact that Ukraine is a cleft country, divided along linguistic and religious lines between eastern Ukraine and western Ukraine, had been known in the West for decades. Less understandable is the Kiev regime’s insistence to keep within its borders some 25 percent of its territories in the east - namely the Donbas - inhabited by a Russian or Russophone majority. Even less reasonable is the attitude of the US administration, which has already spent close to $200 billion to fight a war by proxy against Russia, backing Kiev’s claims to the Donbas and Crimea, which are currently under Russian occupation.

Another question the summit failed to provide an answer to was why Ukraine wasn’t given the choice of joining NATO in exchange for leaving the eastern provinces to the Russians - a solution that was used by the alliance in 1955 when Germany was included in NATO without its eastern part.

One can sensibly argue that by only dangling the prospect of NATO membership in front of Kiev’s eyes, the West is willing to sacrifice another million lives in its fight against Russia, which is callous in the extreme.

The politicians representing EU member states at the summit should have been more open about their interest in solving the union’s eastern frontier problem as soon as possible. Already Ukraine and Moldova have received EU candidate status from Brussels, whereas Georgia - together with Armenia - is most probably going to remain within the Russian sphere of influence. Continuous warfare in Eastern Europe will not bring the frontier issue to a successful resolution anytime soon, only peace negotiations can achieve that.

For NATO and the EU, I would endorse the recent assessment of Nikolas Gvosdev that “whatever the outcome of the Ukraine war, the result will put an end to the expansion of Europe as a geopolitical entity” and I might add, to US unipolarity and hegemonic aspirations in Eurasia.