Is the US Blameless for the War in Ukraine ?

The US-Russia conflict in Ukraine started long before Maidan.

After two and a half years of war in Ukraine, with more than 500.000 dead and wounded, and as a result of intense war propaganda on both sides, the how and the why seem to get distorted on a daily basis in the public sphere, that is when they receive a mention at all.

Most analysts deny any US responsibility for the 2022 Russian armed intervention in Ukraine and argue strongly that it was “unprovoked”. Realist IR experts and analysts, like John Mearsheimer and others, like to date the start of the conflict as the Maidan uprising of 2014 and they tend to blame it on NATO’s eastward expansion. To be sure, those two events are the most immediate ones which precede the annexation of Crimea in 2014, and of the Donbas in 2022.

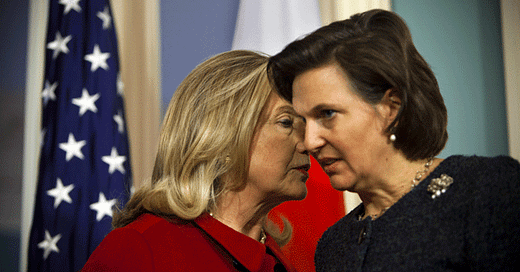

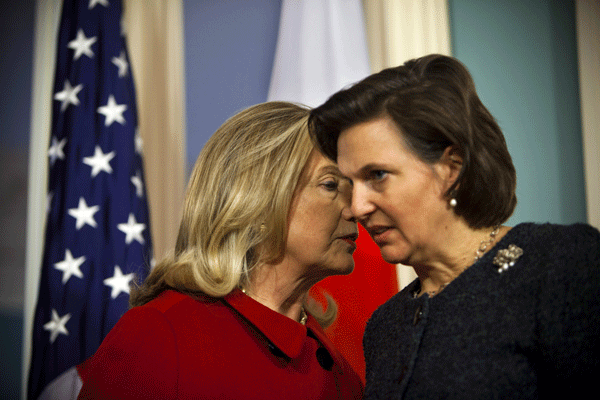

Quite a few European journalists, on the other hand, point the finger at Victoria Nuland’s interference in Ukraine’s internal affairs for the carnage that has happened since.

I’m not known for being a supporter of State Department bureaucracy in general, or of Nuland in particular.

The fact is, however, that in 2014 the geopolitical confrontation between the US and Russia only exploded out into the open. The tug of war between the two powers goes back as far as 2004 and the first Western-sponsored “Orange” revolution.

Although that event brought to power Viktor Youshchenko, a pro-Western president, his initial bid to integrate Ukraine into NATO failed in 2008. In 2010, Ukraine voted to elect a more pro-Russian president, Viktor Yanukovich.

Compared to the current Democrat administration, Bill Clinton’s presidency had been blessed with the presence on his team of much better-equipped professionals to deal with Ukraine, Russia and Eurasia relations. One such bureaucrat, Mark Medish, summed up the problems facing Ukraine in an article from December 22, 2009 published in International Herald Tribune:

“Russia and the United States tend to view Ukraine as a key battleground in a cosmic proxy war between East and West. Both have a bad habit of trying to pick winners in Ukrainian politics. These interventions, naive in their own ways, tend to backfire, often at Ukraine’s expense.” (“The Difficulty of Being Ukraine”)

Western analysts also tend to forget or ignore altogether Hillary Clinton’s contribution in igniting the crisis with Russia in the first place.

By 2012, Vladimir Putin adopted Nursultan Nazarbayev’s project for the creation of an Eurasian Union, in which he intended to include Ukraine. It was ultimately this desire of the Russian leader which fuelled the Maidan protests 2 years later and led to the overthrow of the Yanukovich administration.

Mrs. Clinton’s role in this chain of events started in Dublin in 2012. While attending an OSCE conference, she made it clear that the US (presumably meaning mostly herself) was opposed to the creation of the Eurasian Union, and wrongly claimed it was “a move to re-Sovietize the region”. Sadly, today the same line of argument is being peddled by the Biden administration on every occasion.

The reply to this inept accusation came in a learned article written in 2012 by Nikolas K. Gvosdev, a Security Studies professor at the US Naval War College:

“The US position, as stated by Clinton, is that Washington would not like to see any sort of Eurasian Union emerge, in any way, shape or form. Given the process already underway, in terms of forging closer economic links between Russia and other post-Soviet states, this is not a realistic approach to take. Instead, US policymakers should be asking themselves two questions: is the cooperation proffered by Moscow on other issues of concern to the US of sufficient value to accept a greater degree of Russian influence and control in the Eurasian space ? And are fundamental US interests, as opposed to American preferences, threatened if Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan adopt institutions modelled on the European Union ?

If the answers to the previous questions are yes and no, respectively, shifting the US position from all-out opposition to any form of Eurasian integration in favour of a process that builds stronger protections for individual states’ sovereignty and preserves some degree of openness in the Eurasian space for countries to have trade and security relationships with the West, makes more sense. An Eurasian Union that is simply a more developed customs union in which post -Soviet states freely participate - in part because the free flow of goods, capital and labor across the Eurasian space makes good economic sense for all parties concerned - should not be viewed in the same vein as attempts to forcibly recreate the Soviet Union.

If the Obama Administration adopts this more flexible position, then it will be able to manage the tension between the Russian preference for a more consolidated Eurasian space and the US desire of preserving the independence of the post-Soviet states. But if [Hillary] Clinton’s position, as expressed in Dublin, is enshrined as the US perspective, this will become an area for conflict between the two countries, one that would very likely nullify the reset once and for all.” (“US Stance on Eurasian Union Threatens Russia Reset”)

Needless to say, Gvosdev’s well-argued, even prophetic article was totally ignored by the State Department and its boss Hilary Clinton, who on most occasions botched the issues at hand. From her 2012 performance, to that of Victoria Nuland’s in 2014, to the policy steps adopted by the State Department during the Biden administration, there is a continuity of catastrophic decisions concerning Ukraine.

The political regime brought to power in Ukraine with American help after the Maidan uprising in 2014 was utterly rejected as too nationalistic by the Russophone population from Donbas. As a consequence, an 8-year long guerrilla war developed between the Kiev regime and eastern Ukraine which claimed 11,000 lives, all this before the 2022 Russian military intervention started.

Since 2014, the underlying fact that there is a civilisational fault line in Ukraine between its western and eastern parts, one that was first highlighted by Samuel Huntington in his Clash of Civilisations, has made it impossible for that state to continue its existence in its current boundaries. The Minsk agreements negotiated by EU leaders with Putin notwithstanding, successive leaders in Kiev since 2014 have refused any alternative institutional formula that could have prevented an eventual break-up of the country along linguistic and cultural lines.

This possible partition of the country was foreseen by two historians and geopoliticians, James D. Hardy and Leonard J. Hochberg, who together wrote a series of articles starting in May 2014 on the Ukrainian situation. Taking into account the Donbas insurrection and the refusal of the Russian-speaking population to accept Kiev’s leadership, the two experts outlined a so-called Plan B:

“It is Plan B. But a least worst position is not by definition either unreasonable, nor undesirable. In this case, a divided Ukraine - provided the border is along the civilisation all fault line- between Russia and the West makes sense on every level. It reduces tensions, encourages economic growth, takes account of real, not artificial, cultural and ethnic borders, increases the chances for Russian-European cooperation, prevents Ukrainian disintegration, and rescues America from another foreign policy blunder. A partial win, all around.” (“The Ukrainian Crisis, Part 3 - the Deal”)

As we all know by now, sensible diplomatic solutions to the carnage in Ukraine continue to be rejected out of hand, both by the current Kiev regime and by the Biden Administration.

The point to be grasped, however, is that sooner or later reality on the ground will force the adoption of a solution which takes into account the very real civilisational fault lines that exist in Ukraine. To be sure, no IR expert or Western foreign policy analyst worth their name could then continue to overlook how the war started, why, as well as the possible solutions to bring it to an end.